Domain Name System (DNS) - A Comprehensive Guide

Explore the Domain Name System, its architecture, and how it translates human-friendly domain names into IP addresses.

The Internet’s Essential Directory Service

DNS is a hierarchical naming system built on a globally distributed database. Its core function is to translate memorable domain names (like facebook.com ) into numerical IP addresses required by computers to locate and connect to resources. This translation process is often likened to a network “phone book” or the “GPS for the internet” enabling intuitive navigation.

What is the Domain Name System (DNS)?

DNS is a naming database where internet domain names are stored and translated into IP addresses. It maps the names people use to find a website to the specific IP address that computers use to locate that website.

Without DNS, accessing online resources would require memorizing and inputting lengthy numerical sequences for every website.

The Fundamental Purpose of DNS

The primary objective of DNS is to simplify the user experience by abstracting complex numerical IP addresses. DNS converts a human-readable domain name into the specific IP address required to load internet resources. This conversion sequence is known as DNS resolution. DNS is indispensable for nearly all internet activities, from web browsing to email routing.

A Brief Historical Context of DNS

In the early days, domain names and IP addresses were manually assigned in a centralized file called hosts.txt . As the internet grew, this approach became unsustainable, leading to the development of DNS in 1983 by Paul Mockapetris. DNS introduced a distributed, hierarchical system, enabling the internet’s global scale. The original design prioritized ease of communication over security, creating vulnerabilities that later required solutions like DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC).

Core Components of the DNS Infrastructure

DNS operates through several key components, each playing a distinct role in translating domain names into IP addresses.

Key DNS Components:

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| DNS Resolver | Handles client queries, checks cache, queries Root/TLD/Authoritative |

| Root DNS Servers | Top of hierarchy, directs to TLD servers |

| TLD Servers | Manage TLDs, direct to authoritative servers |

| Authoritative Servers | Store official DNS records for domains |

| DNS Protocol Port | Standard communication port (UDP/TCP 53) |

The DNS Resolution Process

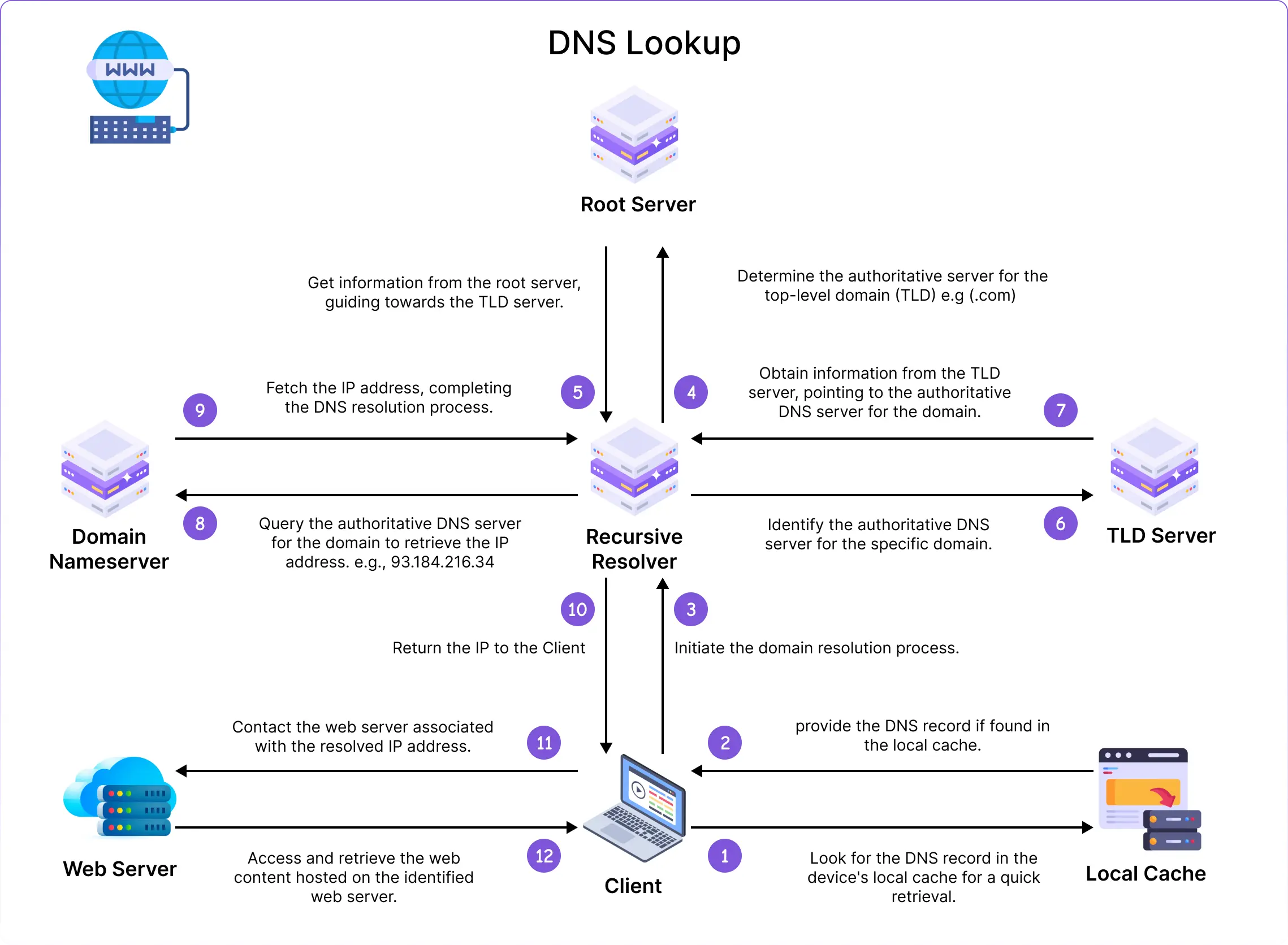

DNS resolution taken from Amigoscode

DNS resolution taken from Amigoscode

- Check Local Cache (Steps 1–2)

The client first checks its local DNS cache for the IP address of the domain.- ✅ If found: Uses the cached IP address immediately.

- ❌ If not found: Proceeds to contact a recursive DNS resolver.

Query Recursive Resolver (Step 3)

The client sends a query to the recursive resolver to resolve the domain name (e.g.,example.com).Recursive Resolver Contacts Root Server (Steps 4–5)

The recursive resolver queries a root DNS server, which responds with a reference to the appropriate Top-Level Domain (TLD) server (e.g., for.comdomains).TLD Server Points to Authoritative Nameserver (Steps 6–7)

The resolver queries the TLD server, which replies with the address of the authoritative nameserver for the requested domain.Get IP from Authoritative Nameserver (Steps 8–9)

The recursive resolver queries the authoritative nameserver, which responds with the IP address for the domain.- Return IP & Connect to Web Server (Steps 10–12)

The resolver returns the IP address to the client. The client then uses this IP to contact the web server and retrieve the website content.

Caching at various levels (browser, OS, resolver) is essential for performance, reducing latency and network load.

DNS Record Types

Authoritative DNS servers store various DNS records, which are the building blocks for directing internet traffic.

Some common DNS record types include:

| Record Type | Function | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| A | Maps domain to IPv4 address | Website server location |

| AAAA | Maps domain to IPv6 address | IPv6 website server location |

| CNAME | Alias from one domain to another | Pointing www.example.com to example.com |

| MX | Specifies mail servers | Email delivery |

| NS | Delegates DNS zone to authoritative servers | DNS management |

| SOA | Stores zone administrative info | Zone transfers, updates |

| SRV | Locates specific services | Service discovery |

| PTR | Maps IP to domain (reverse DNS) | Email validation |

| TXT | Stores text info | SPF, domain verification |

DNS Caching

DNS caching is a mechanism that temporarily stores DNS query results at multiple points in the network path—such as browsers, operating systems, and DNS resolvers—to accelerate domain resolution and reduce unnecessary network traffic.

How DNS Caching Works

When a DNS query is resolved, the resulting IP address and related records are stored in a cache for a specified period. If the same domain is requested again before the cache expires, the system retrieves the answer from the cache instead of repeating the entire DNS resolution process. This reduces lookup times and network load.

Benefits of DNS Caching

- Faster Resolution: Cached responses eliminate the need for repeated queries, minimizing latency and improving user experience.

- Better Online Experiences: Faster DNS lookups lead to quicker page loads and smoother browsing.

- Traffic Optimization: Reduces redundant queries to upstream DNS servers, optimizing network efficiency.

- Bandwidth Conservation: Fewer DNS requests mean less bandwidth consumption, especially important for large organizations or ISPs.

- Offline Access: Cached records may allow access to previously visited sites even if the DNS server is temporarily unreachable.

- Optimal Distribution: Distributes DNS query load across the network, improving scalability and resilience.

DNS Cache Hierarchy

DNS caching occurs at several layers, each with its own scope and lifespan:

- Browser Caching: Most modern browsers maintain their own DNS cache for recently visited domains, providing the fastest possible lookups.

- Operating System (OS) Caching: The OS maintains a system-wide DNS cache, serving all applications and reducing repeated queries to external resolvers.

- DNS Server (Resolver) Caching: Recursive DNS resolvers cache responses for all clients, significantly reducing the number of queries sent to authoritative servers.

Time-to-Live (TTL) and Cache Management

Each DNS record includes a Time-to-Live (TTL) value, which specifies how long the record should be considered valid and kept in cache. Longer TTLs improve speed and reduce DNS traffic but may delay the propagation of updates (such as IP address changes). Shorter TTLs ensure fresher data but increase the frequency of DNS queries, potentially adding load to DNS infrastructure.

Administrators must balance TTL settings based on the desired trade-off between performance and update responsiveness.

DNS Load Balancing and Failover

DNS Load Balancing

DNS load balancing distributes incoming client requests across multiple servers by returning different IP addresses for the same domain name, often using round-robin, geo-location-based, or weighted algorithms. This helps prevent server overload, optimizes resource utilization, and enhances application performance and reliability.

- Round-Robin: Cycles through a list of IP addresses for each query.

- Geo-location-based: Directs users to the nearest server based on their geographic location.

- Weighted: Assigns more traffic to servers with higher capacity or availability.

DNS Failover

DNS failover is a technique that ensures high availability by automatically redirecting traffic from an unavailable or unhealthy server to a backup server. This is typically achieved by monitoring server health and updating DNS records when a failure is detected, minimizing downtime and maintaining service continuity.

The Synergy of Load Balancing and Failover

Load balancing and failover work together to maximize uptime and performance. Load balancing proactively distributes traffic to prevent overload, while failover reactively reroutes traffic during server outages. Combined, they provide robust resilience against both routine load spikes and unexpected failures.

Limitations of DNS Load Balancing

- Not Inherently Load-Aware: DNS does not monitor real-time server load; it only distributes queries based on predefined rules.

- No Native Failure Detection: DNS alone cannot detect server failures without external health checks and automation.

- TTL Propagation Delays: Changes to DNS records (such as during failover) may not take effect immediately due to cached records with unexpired TTLs.

- Uneven Propagation Across ISPs: DNS updates may propagate at different rates across networks, leading to inconsistent user experiences.

For real-time, dynamic traffic management and granular health checks, dedicated application load balancers or traffic managers are often used alongside DNS-based solutions.

Vulnerabilities and Protective Measures

Inherent Vulnerabilities of Early DNS Design

Early DNS prioritized ease of communication over security, accepting answers without verification. This created vulnerabilities like spoofing and cache poisoning.

Common DNS Attacks

- DNS Spoofing/Cache Poisoning: Injecting forged data to redirect users.

- DNS Hijacking: Redirecting queries to malicious servers.

- Denial-of-Service (DoS) Attacks: Overwhelming DNS servers with traffic.

- DNS Amplification Attacks: Using open resolvers to flood victims.

- NXDOMAIN/Phantom Domain/Random Subdomain Attacks: Exhausting server resources.

- DNS Tunneling: Exfiltrating data or bypassing firewalls via DNS queries.

DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC)

DNSSEC enhances DNS security by adding authentication and validation using digital signatures and a hierarchical chain of trust, protecting against spoofing and man-in-the-middle attacks.

| Vulnerability/Attack Type | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| DNS Spoofing/Cache Poisoning | Forged data in resolver’s cache | Redirection, malware, phishing |

| DNS Hijacking | Redirects queries to malicious server | Unauthorized control, reputational/financial loss |

| DNS Tunneling | Embeds protocols in DNS queries | Data exfiltration, malware C2 |

| DNS Amplification (DDoS) | Floods victim with excessive traffic | Service outages, denial of service |

| NXDOMAIN/Phantom/Random | Floods with non-existent/slow domains | DoS, slow performance, service degradation |

Private DNS

What is Private DNS?

Private DNS refers to a DNS system managed within an organization or private network, rather than relying solely on public DNS servers. It enables the resolution of internal domain names—such as intranet.company.local—that are not accessible or visible on the public internet.

How Private DNS Works

A private DNS server acts as the authoritative source for internal domain names, mapping them to internal IP addresses. This setup is often integrated with DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol), which automatically assigns IP addresses to devices and updates DNS records accordingly. When a user or device queries an internal domain, the private DNS server responds directly, bypassing public DNS infrastructure.

Benefits of Private DNS

- Enhanced Security: Internal DNS queries and records remain within the organization, reducing exposure to external threats.

- Greater Control: Organizations can define custom domain structures and policies tailored to their needs.

- Improved Performance: Local resolution reduces query latency and network traffic.

- Increased Privacy: Sensitive internal network information is not leaked to public DNS servers.

- Customization: Supports unique naming conventions and integration with internal services.

Common Private DNS Architectures

- Dedicated Internal DNS Servers: Standalone servers that handle all internal DNS queries.

- Split-Horizon DNS: Provides different DNS responses based on the source of the query (internal vs. external), ensuring internal names are only resolvable within the network.

- DNS Forwarding: Internal DNS servers forward queries for external domains to public resolvers, while handling internal domains locally.

- Integration with SDN or Cloud DNS: Modern networks may use software-defined networking (SDN) or cloud-based DNS solutions for flexible, scalable management.

Conclusion

DNS is the backbone of modern internet communication, seamlessly translating human-friendly domain names into machine-readable IP addresses. Its hierarchical architecture, caching strategies, and diverse record types ensure efficiency and reliability. While early design choices introduced vulnerabilities, advancements like DNSSEC have significantly improved security. Private DNS further extends DNS capabilities, granting organizations greater control, privacy, and customization. As the internet evolves, DNS remains essential for secure, efficient, and scalable connectivity.